4th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 29 :: Joanna C. Valente on John Milton

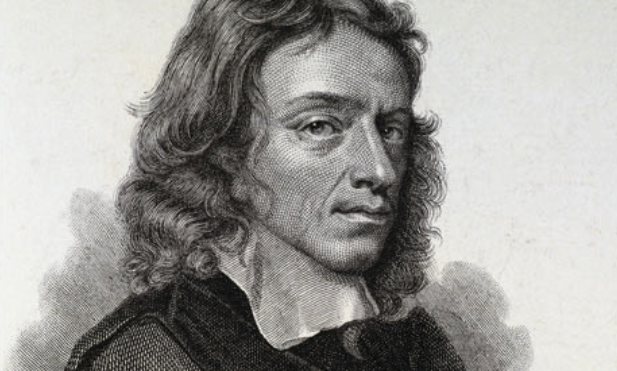

[line]Sometimes I like to think John and I are best friends, that we take long walks in Prospect Park together, looking like an old married couple as I momentarily guide him, work as his non-poetic eye. Of course, Milton was born exactly 381 years before I was even a thought floating across the universe; a fellow Sagittarian and rebel, he abandoned plans to enter the clergy, and instead became a poet. Clearly, he is a man after my own heart—a man whose mind created one of the most breathtaking and controversial epics in the world: Paradise Lost.

[line]Sometimes I like to think John and I are best friends, that we take long walks in Prospect Park together, looking like an old married couple as I momentarily guide him, work as his non-poetic eye. Of course, Milton was born exactly 381 years before I was even a thought floating across the universe; a fellow Sagittarian and rebel, he abandoned plans to enter the clergy, and instead became a poet. Clearly, he is a man after my own heart—a man whose mind created one of the most breathtaking and controversial epics in the world: Paradise Lost.

Who decides to write a poem centering on Satan as a protagonist? That’s right—John Milton. Clearly, he was not afraid of the Church’s reaction to the theological themes, political commentary and cultural criticism the text poses; like the tragic prophet Tiresias, Milton lost his eyesight by his mid-forties—working as a kind of poetic prophet himself—retelling Christianity’s religious past in order to understand humanity in the present, perhaps as a way to cobble together a future.

As an undergraduate, I was entirely too lucky to study Milton under the brilliant Bob Stein, whose passion and knowledge of Milton’s entire lexicon is not just astounding, but contagious. I fell in love with Paradise Lost within the first line of the text: “Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit.” In iambic pentameter, Milton is not only able to summarize Adam and Eve’s fall, but erotizes the fruit, engages the reader with the suspense of temptation—temptation and sin at the forefront of the text, and of our past & present world.

Having grown up in a conservative Greek Orthodox family while also attending Catholic primary school, I developed a keen interest with Christian iconography and mysticism; I am not a particularly religious person and identify as agnostic, but couldn’t help but be transfixed by its supernatural and strange aesthetic. As a woman, Mary mystifies me—at once she is perfect and pure and kind and motherly; yet, the idea that she gave birth to the son of God, that she became a wife, that her body ascended to heaven are downright strange, if not what I would consider witchy.

Studying Christianity as a child, I never quite bought into the idea that Lucifer was merely a fallen angel who became the epitome of evil, a sublime void; instead, I tended to prefer the more nuanced, Old Testament version where he acts as a foil to God, as the ultimate challenger. This job in itself, to challenge God, is not actually evil—it’s much more complicated than a third grader’s black-and-white fairy tale version. It presents Satan more as a frenemy, in some ways, daresay an equal, in the Book of Job:

[articlequote]Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the LORD, and Satan came also among them… Then Satan answered the LORD, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it. And the LORD said unto Satan, Hast thou considered my servant Job, that there is none like him in the earth?” (King James Bible, 6-8).[/articlequote]

Of course, when I began reading PL, I was mesmerized. Milton hits us continuously with iamb after iamb, beating our hearts continuously into the fruit of the text. In the fourth book, Satan is completely and devastatingly tormented with his fate, knowing he will be forever everything that God is not:

[box]

“Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrauth and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;

And, in the lowest deep, a lower deep

Still threatening to devour me opens wide,

To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heaven.

O, then, at last relent! Is there no place

Left for repentence, none for pardon left?” (5-12)

[/box]

We, as humans, cannot truly wrap our heads around the concept of eternal misery, but we can all sympathize with the quintessential underdog, as we are all the underdog in our own story. Milton masterfully leaps from moments of sheer isolation and grotesque sorrow to portraits of ethereal beauty, as in the eighth book when Raphael describes angel love-making:

[box]

“To whom the Angel, with a smile that glowed

Celestial rosy-red, Love’s proper hue,

Answered:—“Let it suffice thee that thou know’st

Us happy, and without Love no happiness.

Whatever pure thou in the body enjoy’st

(And pure thou wert created) we enjoy

In eminence, and obstacle find none

Of membrane, joint, or limb, exclusive bars.

Easier than air with air, if Spirits embrace,

Total they mix, union of pure with pure

Desiring, nor restrained conveyance need

As flesh to mix with flesh, or soul with soul,” (618-629).

[/box]

These are not just exquisite lines of poetry, but have influenced my entire belief system: in my own relationships, whether platonic or romantic, I seek to be as open and compassionate and full of love as I can humanly be, to aspire to a complete mind-body connection that fulfills me.

Of course, this realization did not come easily, or as fast as reading the lines themselves. It took years for me to become comfortable with myself—a process all artists must make as they face adversity from their peers. The proverbial light bulb may have went off as I highlighted the pages in the text at age twenty, but didn’t quite sink in until years later, when I was truly coping with an assault and defining my belief structure as a woman.

Like a reoccurring dream, I kept remembering lines from Paradise Lost, returning to it like a lost hometown as I was writing through my own trauma, identifying with Satan. I felt isolated, wronged, and just plain bad, even though I was not the cause of it; I carried around a bellyful of guilt, as Sin gave birth to Death after being raped by Satan—which is reflective of the treatment of women in past & present societies.

In book two, Sin’s grotesque physical transformation when becoming pregnant and nightmarish reoccurring birth not just symbolize a reverse motherhood, but of the emotional ramifications of rape and abuse—of the never ending memories:

[box]

“breaking violent way,

Tore through my entrails, that, with fear and pain

Distorted, all my nether shape thus grew

Transformed: but he my inbred enemy

Forth issued, brandishing his fatal dart,

Made to destroy. I fled, and cried out Death!

[…]

And hourly born, with sorrow infinite

To me: for, when they list, into the womb

That bred them they return, and howl, and gnaw

My bowels, their repast; then, bursting forth

Afresh, with conscious terrors vex me round,” (780-789).

[/box]

When I think of fruit, I think of transformation: a beginning, then a blossoming. I think of Milton, in many ways, holding my hand to a new beginning at the end of a park.

[line][line][textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/joanna_vertical-e1430148495666.jpg[/textwrap_image]JOANNA C. VALENTE is sometimes a mermaid and sometimes a human. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014) and received her MFA at Sarah Lawrence College. Her second collection Marys of the Sea is forthcoming from ELJ Publications in 2016. Some of her work appears, or is forthcoming, in The Huffington Post, Columbia Journal, Similar Peaks, The Paris-American, The Atlas Review, The Destroyer, among others. In 2011, she received the American Society of Poets’ Prize. She founded Yes, Poetry in 2010,and is the Managing Editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

[line] [h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5] [mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”] [line] [recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]