6th ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 11 :: Travis Sharp on Cecilia Vicuña

[box][blockquote]HAPPY POETRY MONTH, FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

For this, the 6th Annual iteration of our beloved Poetry Month 30/30/30 series/tradition, I asked four poets (and previous participants) to guest-curate a week of entries, highlighting folks from their communities and the poets who’ve influenced their work.

I’m happy to introduce Janice Sapigao, Johnny Damm, Phillip Ammonds, and Stephen Ross, who have done an amazing job gathering people for this years series! We’re so excited to share this new crop of tributes with you. Hear more from our four guest editors in the introduction to this year’s series.

Hungry for more? there’s 150 previous entries from past years here! You should also check out Janice’s piece on Nayyirah Waheed, Johnny’s piece on Raymond Roussel, Phillip’s piece on Essex Hemphill, and Stephen’s piece on Ronald Johnson’s Ark, while you’re at it.

This is a peer-to-peer system of collective inspiration! No matriculation required.

Enjoy, and share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/blockquote][/box]

[line][line]

[box] WEEK TWO :: CURATED BY JOHNNY DAMM

PROPOSITION:

Every time a WRITER sees another WRITER on the street, WRITER # 1 yells the following question:

“Who are you reading?”

WRITER # 2 answers, also yelling, and at the first word, EVERYONE on the street stops walking, presses hands over mouths of cooing/crying babies, slams down car brakes and hurriedly unrolls windows.

EVERYONE listens, the world not allowed to resume until WRITER # 2 stops yelling.

SMALL REVISION:

Keep everything exactly the same, except make sure that WRITER # 2 is a talented writer, a fascinating writer, that WRITER # 2 is the present or future of what literature should be.

PROPOSITION:

Hush, y’all. Listen as Colette Arrand, Stephen Emmerson, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, E.G. Cunningham, Douglas Luman, Travis Sharp, Raquel Salas Rivera, and Terri Witek yell into the street. [line]

Johnny Damm is the author of Science of Things Familiar (The Operating System, 2017) and three chapbooks, including Your Favorite Song (Essay Press, 2016), and The Domestic World: A Practical Guide (Little Red Leaves, forthcoming). His work has appeared in Poetry, Denver Quarterly, the Rumpus, Drunken Boat, and elsewhere. Visit him online at johnnydamm.com. [/box]

[line][line]

Travis Sharp on Cecilia Vicuña

[line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Screen-Shot-2017-03-24-at-7.14.27-PM-e1490397365232.png[/textwrap_image]To prepare for an MFA seminar in Bothell, Washington, Sarah Dowling requested that we collect some garbage and bring it to class. Or did Sarah bring the garbage? Or we found it somewhere on campus? Somehow the garbage arrived in class with us. We were reading excerpts from Spit Temple, the collection of performances and autobiographical notes of Cecilia Vicuña (edited and translated by Rosa Alcalá). We were reading about Vicuña’s life in snippets, reading transcriptions of her performances, watching a video of Vicuña crisscrossing a rocky terrain with red thread. Images of thread spread across a river, Vicuña weaving an audience with thread as she speaks. Around us there was garbage on the tables, and together we created little precarios, some basuritas that we carefully curated from the piles. We later placed these around campus, later to be knocked down by undergrads or thrown away by the cleaning staff. (A group of us curated the honey-pot-bear-ink-cartridge-crushed-red-peppers-cardboard-string-stick and left it on a pool table outside the seminar room.)

I’m shaped most by this ephemeral quality of Vicuña’s work: her interest in the disappeared and in the not-yet-emerged, and her careful curation-creation of art that is designed to dissolve. (Or, is aware of its inevitable dissolution? In the end, everything is auto-destructive.) I’m interested in the proliferative potential of this ephemerality—how, despite its intended degradation, the ephemeral object makes itself known in its smallness. Vicuña’s basuritas rafts floating atop street puddles in New York.

[line]

[script_teaser]Vicuña in ‘Spit Temple’:[/script_teaser]

[articlequote]I felt the wind and the sea feeling me. I knew I had to respond to the Earth in a language that the tide would erase. I arranged the litter I saw strewn about. I called it ‘arte precario’ knowing that art had begun in me” (55). [/articlequote]

[line]

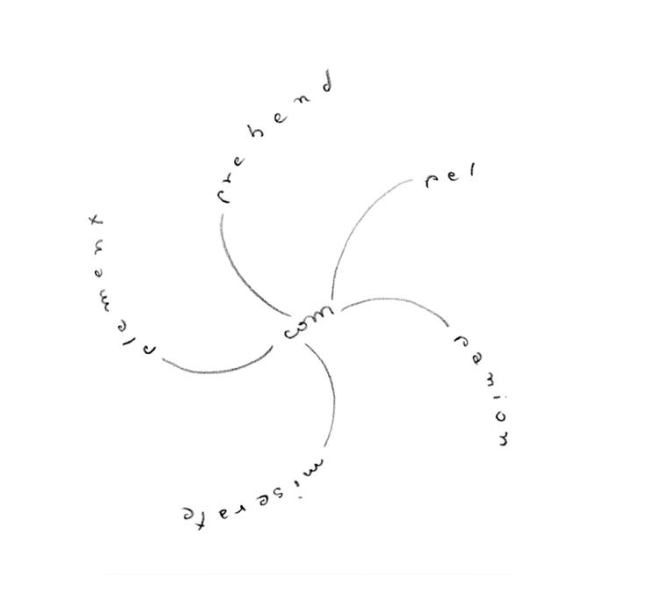

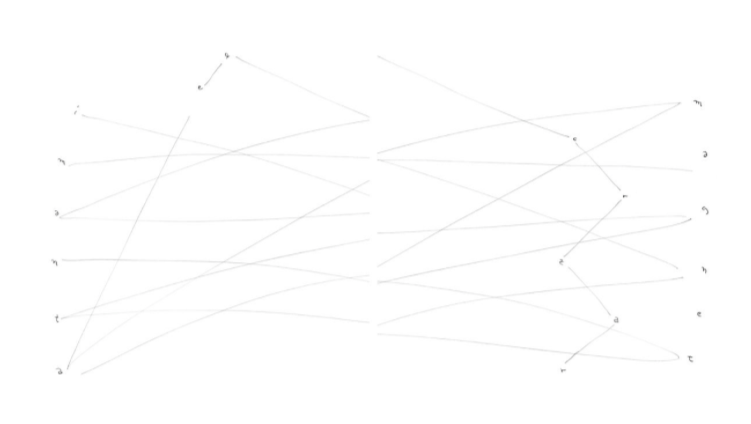

[textwrap_image align=”right”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Screen-Shot-2017-03-24-at-7.21.01-PM-e1490397878620.png[/textwrap_image]Kenneth Sherwood defines Vicuña’s actions/performances not as improvisations but as listenings—and a connection is drawn between Vicuña’s sense of listening and Spicer’s notion of the poet-radio. Vicuña, in ways more tangible than Spicer’s notion of dictation, is listening in her performances (and thinking of listening as a form of responding). She is responding to the audience responding, responding to the space of the performance and its idiosyncrasies, responding to previous manifestations of the performance, responding to “the fertility of words” and the positive potential within the productive rupture of words. Vicuña’s quipu threads could be conduits for the motion of energy (in performances, wrapped around the audience, binding them together, breathing together, all of a body), like Rayonist rays of color and light, connecting those who see in unanticipated vectors. [line]

[line]

Vicuña writes of her Quasars in Spit Temple: “At some point, I began tying the audience with threads, or tying myself to the audience. Who is performing: the poet, or the audience? United by a thread, we form a living quipu: each person is a knot, and the performance is what happens between the knots” (99).

[line]

[box]From “Entering” in The Precarious:

“First there was listening with the fingers, a sensory memory: / the shared / bones, sticks and feathers were sacred things I had to arrange. // To follow their wishes was to rediscover a way of thinking: the / paths of mind I traveled, listening to matter, took me to / an ancient silence waiting to be heard. // To think is to follow the music, the sensations of the elements. // And so began a communion with the sky and the sea, the need / to respond to their desires with works that were prayers” (131). [/box]

[line]

I’m reminded of another text Myung Mi Kim referenced in a seminar last semester, Gramática de la lengua castellana by Antonio de Nebrija and published in 1492. A selection: “After Your Highness has subjected barbarous peoples and nations of varied tongues, with conquest will come the need for them to accept the laws that the conqueror imposes on the conquered, and among them our language; with this work of mine, they will be able to learn it, as we now learn Latin from the Latin Grammar”; “Language has always been the perfect instrument of empire.”

Yes. And Vicuña’s productive rupture or opening-up of language, palabrarmas, through her excavation of the threads, lineages, and etymologies secreted away within their material, connotative, and denotative structures could be seen as a form of resistance to language’s imperial instrumentality (or, its insistent reification of the lisible, which is put to use as a perpetuation of itself and of empire). Weaving connections interlingually, Vicuña foregrounds the etymological proliferation essential to language lineages and keeps the instrumentality of language off balance. That is to say that Vicuña’s threading of language forecloses imperial instrumentality in that it disallows language to exist as a solid force: it questions the intelligibility of the established modes of discourse by way of productive linguistic rupture, upending monolithic images of what-is-language, upending monolingualism, upending the lisible, and opening-up radically to the illisible, the not-recognized, in the ways in which it shifts its focus to the unseen, to the seeing that is no longer seen, and to the interactivity between writer-reader and reader-writer.

[line]

[articlequote]Vicuña gives us a sense of the invisible, the unseen, (to borrow from Judith Butler) the far side of established modes of intelligibility.[/articlequote]

[line]

I reflect often on the precarios since they provide a sense of Vicuña’s relational art practice. By “relational” I mean in part what Nicolas Borriaud refers to as “relational aesthetics,” or an art which is constituted not in its material manifestation but in the systems of relationships it enacts. Vicuña’s praxis is akin to relational aesthetics but is distinct in its focus on the helical, recursive and reciprocal interactivity of writer-reader, speaker-audience, human-earth. By “helical” I mean that Vicuña’s poetics is one in which hierarchically violent Western metaphysical binaries cannot hold weight.

[box]From “Language Is Migrant”:

“I ‘wounder,’ said Margarita, my immigrant friend, mixing up wondering and wounding, a perfect embodiment of our true condition!”[/box]

[line]

[line]

Vicuña’s helical works—especially her performances—are called “Quasars.” I think of Vicuña’s notion of the Quasar as taking part in what Halberstam in “Queer Temporalities and Postmodern Geographies” calls “the potential to open up new life narratives and alternative relations to time and space” (364). Quasars, in the literal sense, are distant celestial objects which cast off enormous amounts of energy and which are widely considered to be spaces of origination for future galaxies. The use of the figure of the Quasar in Vicuña’s poetics is significant in that it calls to attention to stark distinction between what is humanly experienced and what is—the distinction between a Quasar in the sky, seen by a human, blinking softly, and the Quasar itself casting out energy at a level unimaginable (to think that it can sustain itself while also dispersing itself in such quantities). This stark distinction exists within the question of lisibility: who/what/where/when exists on the far side of established modes of intelligibility, and by what means can the illisible—those who are not immediately considered “subject”—break through the already-recognized and be seen not as a feeble flicker but as a Quasar?

As I’m writing this my parents text me. They are concerned about the wind chill and the levels of snow in Buffalo. They are concerned about immigration and the economy and are very excited by the recent election. They are concerned about my queerness my genderlessness about my clothes about my hair about my voice about my Facebook posts. I’ve been searching for an email my mother sent me when she discovered my first boyfriend in high school (I want to mine it for language), but I can’t find it. But I can feel it, my parents’ invisibilizing of me becoming an invisibilizing of myself. I wrote in a recent poem: “Define erase. An erase is an opening in the body, a gape of one’s own making. Use erase in a sentence. I became an erase. I had a nightmare in which I erased body. I am gaping yet mobile. I was disappeared but vocal.”

I write poems to Quasar myself.

[box]

Vicuña writes in “Language Is Migrant”:

In the film people in the street improvise responses on the spot, displaying an awareness of language that seems to be missing today. I wounder, how did it change? And my heart says it must be fear, the ocean of lies we live in, under a continuous stream of doublespeak by the violent powers that rule us. Living under dictatorship, the first thing that disappears is playful speech, the fun and freedom of saying what you really think. Complex public conversation goes extinct, and along with it, the many species we are causing to disappear as we speak.

The word “species” comes from the Latin speciēs, “a seeing.” Maybe we are losing species and languages, our joy, because we don’t wish to see what we are doing.

Not seeing the seeing in words, we numb our senses.

I hear a “low continuous humming sound” of “unmanned aerial vehicles,” the drones we send out into the world carrying our killing thoughts.

Drones are the ultimate expression of our disconnect with words, our ability to speak without feeling the effect or consequences of our words.

[/box]

[line]

Under the weight of dominant discourse and the force of the lisible, how can we come to see the seeing in words? “I wounder.”

(Image credit: Images 2-4 are from ceciliavicuna.com. Images 3-4 are originally from Instan by Cecilia Vicuña.

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Screen-Shot-2017-03-24-at-7.27.04-PM-e1490398058903.png[/textwrap_image] Travis Sharp is a queer poet, book artist, and editor at Essay Press. Travis is also part of the Letter [ r ] editorial collective and is a PhD student in the Poetics Program at the University at Buffalo. Travis’ writing has appeared with Columbia Poetry Review, Puerto del Sol, LIT, Bombay Gin, The Conversant, and elsewhere. Alongside Aimee Harrison and Maria Anderson, Travis co-edited Radio: 11.8.16 (Essay Press, 2017), a collection of essay responses to the 2016 US presidential election.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]