6th ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 24 :: AARON BELZ on BLY's VALLEJO

[box][blockquote]HAPPY POETRY MONTH, FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

For this, the 6th Annual iteration of our beloved Poetry Month 30/30/30 series/tradition, I asked four poets (and previous participants) to guest-curate a week of entries, highlighting folks from their communities and the poets who’ve influenced their work.

I’m happy to introduce Janice Sapigao, Johnny Damm, Phillip Ammonds, and Stephen Ross, who have done an amazing job gathering people for this years series! We’re so excited to share this new crop of tributes with you. Hear more from our four guest editors in the introduction to this year’s series.

Hungry for more? there’s 150 previous entries from past years here! You should also check out Janice’s piece on Nayyirah Waheed, Johnny’s piece on Raymond Roussel, Phillip’s piece on Essex Hemphill, and Stephen’s piece on Ronald Johnson’s Ark, while you’re at it.

This is a peer-to-peer system of collective inspiration! No matriculation required.

Enjoy, and share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/blockquote][/box]

[line][line]

[box]

WEEK 4 :: CURATED BY STEPHEN ROSS

The community of poets and scholars convened here for the OS’s National Poetry Month has never existed, as far as I know, in the same geographical or electronic space. Yet I’m moved to see that the members of this new community (excluding the New Yorkers) all hail from the places I’ve lived that mean the most to me: Montreal, the UK Midlands, North Carolina, Georgia. I canvassed old friends and new acquaintances, as well as friends of friends, to contribute to this year’s Poetry Month, and am delighted to find how meaningfully the contributions resonate with each other. These mutually reinforcing energies are not simply a matter of aesthetic and/or political affinities between the poet-scholars and their poets, but emerge from each contributor’s recognition and appreciation of the particulars of their chosen poet.

Contributions by Charles Gonsalves (on Barbara Guest), Sarah Huener (on Eileen Myles), and Aaron Goldsman (on Tommy Pico) span three generations of what some might still be pleased to call the New York School–which generation are we on now? Other contributors attend to the limits of poetics: Klara DuPlessis reflects eloquently on Anne Carson’s (de)creative refusal to finish a book, while Zohar Atkins ponders William Bronk’s endless rewriting of the same poem. Aaron Belz’s tribute to Robert Bly’s translations of César Vallejo speaks to the winding, unpredictable process of poetic influence.

Stephen Ross is a literary scholar, translator, and editor. He earned his PhD in English from the University of Oxford in 2013 and is a founding editor of the literary web-journal, Wave Composition. With Ariel Resnikoff, he is working on the first-full length translation and critical edition of Mikhl Likht’s Yiddish modernist long-poem, Processions. He is a contributing editor for The Operating System’s Unsilenced Texts series, and also co-editor with Dr. Alys Moody of the forthcoming anthology, Global Modernists on Modernism (Bloomsbury, 2017), a 190,000-word sourcebook that draws on a large archive of historical materials — statements, manifestos, letters, prefaces, introductions, hybrid works, etc — by modernist practitioners across the arts, with a special focus on untranslated, poorly disseminated (in English), and ‘forgotten’ texts. His current book project is a study of modern American poetics and objecthood.

[/box]

[line][line]

AARON BELZ on BLY’s VALLEJO

[script_teaser]”All I wanted was a poetics that was unafraid to clunk.” [/script_teaser] [line]

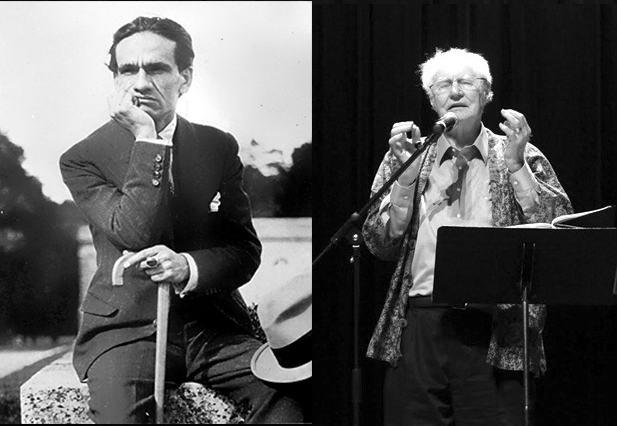

Poems in translation are notoriously hard to discuss, because who wrote them? For example I’ve treasured Robert Bly’s translations of Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo for more than 20 years, even though I’ve heard they’re as much Bly as they are Vallejo. Someone told me Clayton Eshleman’s translations are better, but I find them flat and uninspired. I conclude that I have a personal attachment to Bly’s Vallejo, per se.

I suppose it was 1993 or 1994 when I first picked up Neruda & Vallejo. Robert Bly was, or would soon be, my professor at NYU. He was a jolly and frank man, apple-cheeked and barrel-chested, and seemed to have walked to class from the Minnesotan woods. He wore a colorful Native American vest. He reeked of body odor and loved to hug his students with his strong frontiersman’s arms. He would read a poem to us, wait a couple of beats, and read the same poem again. And sometimes a third time.

I describe Bly’s charisma as evidence that he might not be the most impartial or academic translator. When he translated, he must have been in the translation. I don’t think Bly wrote anything at all without his own powerful musk at work.

Which is all to say that although this book with “Neruda & Vallejo” in large pink letters on its cover and spine, containing translations by not only Bly but James Wright, John Knoepfle, and Douglas Lawder, served as my introduction to a poet who would become immeasurably important to me, such service may have been corrupted by oddball, biased, or otherwise intrusive philosophies of translation. I may have fallen, at least to some degree, for the translators’ charm rather than for the pure fire of the original authors.

By way of counter-caveat, the book does contain all the original texts on its facing pages, so readers can enjoy them in Spanish or try their own hands at translation.

[line]

But it was the translations with which I, personally, fell in love:

[line]

[blockquote]

This afternoon it rains as never before; and I

don’t feel like staying alive, heart.

The afternoon is pleasant. Why shouldn’t it be?

It is wearing grace and pain; it is dressed like a woman.

This afternoon in Lima it is raining. And I remember

the cruel caverns of my ingratitude;

my block of ice laid on her poppy,

stronger than her crying “Don’t be this way!”

My violent black flowers; and the barbarous

and staggering blow with a stone; and the glacial pause. . .

[/blockquote]

[line]

Whew. Vallejo! I read these lines and wondered, how can this exist? Another:

[line]

[blockquote]

I feel that God is traveling

so much in me, with the dusk and the sea.

With him we go along together. It is getting dark.

With him we get dark. All orphans. . .

[/blockquote]

[line]

These are just the beginnings of poems so perhaps you’ll read them to their ends on your own. Here is perhaps my favorite, “The Anger that Breaks a Man Down Into Boys,” in its entirety:

[line]

[blockquote]

The anger that breaks a man down into boys,

the breaks the boy down into equal birds,

and the bird, then, into tiny eggs;

the anger of the poor

owns one smooth oil against two vinegars.

The anger that breaks the tree down into leaves,

and the leaf down into different-sized buds,

and the buds into infinitely fine grooves;

the anger of the poor

owns two rivers against a number of seas.

The anger that breaks the good down into doubts,

and doubts down into three matching arcs,

and the arc, then, into unimaginable tombs;

the anger of the poor

owns one piece of steel against two daggers.

The anger that breaks the soul down into bodies,

the body down into different organs,

and the organ down into reverberating octaves of thoughts;

the anger of the poor

owns one deep fire against two craters.

[/blockquote]

[line]

I read this aloud to someone the other day and he said, “Sounds mathematical.” At first I thought, what an odd response. But it’s correct. Vallejo is actually an algebraic poet, creating a syntax full of variables and assigning to them what appear to be slightly incorrect values. To wit, the first two stanzas of “Poem to be Read and Sung”:

[line]

[blockquote]

I know there is someone

looking for me day and night inside her hand,

and coming upon me, each moment, in her shoes.

Doesn’t she know the night is buried

with spurs behind the kitchen?

I know there is someone composed of my pieces,

whom I complete when my waist

goes galloping on her precise little stone.

Doesn’t she know that money once out of her likeness

never returns to her trunk?

[/blockquote]

[line]

Funny to imagine singing this, especially the closing line: “But she does look and look for me. This is a real story!” But I love it so much. I wouldn’t have become interested in writing my own poetry if not for Vallejo via Bly, or at least not interested in the way I became interested in it, with a passion for strange, surprising syntax that references love and God amid a din of microsymbols. Moments of enlightenment in a whirlwind of worldliness.

Perhaps more importantly, Bly’s Vallejo gave me a voice I’d never heard before in literature. It sounded so personal and direct, while at the same time keenly aware of its own limitations, and it also clunked, strangely. All I wanted was a poetics that was unafraid to clunk. I felt I could be at home there.

[line] [line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Aaron-Belz-e1492130990838.jpg[/textwrap_image] Aaron Belz has published three books of poetry: The Bird Hoverer (BlazeVOX, 2007), Lovely, Raspberry (Persea, 2010), and Glitter Bomb (Persea, 2014). He lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]